Remember the good old days when banks paid 12% or more interest on FDs, there was no TDS or forced PAN connection, no taxes to pay, and the corpus doubled every five to six years.

On top of that, petrol was in single digits, the only snack you could eat was a Samosa, the luxury car was a Maruti 800 or max a Maruti 1000, Levi’s Jeans were the fashion statement, festivals meant the annual purchase of new clothes and shoes, binging was on Peter Scot whisky in summers and Old Monk in winters, eating out was at a Dhaba, summer holidays meant a sojourn in Mussoorie or Simla, winters were for visits to grandparents, and weekends we used to go for a picnic.

The Club Tambola provided the ultimate amusement, with the newest blockbuster movies available in “air-cooled” cinema halls for Rs 3 per ticket, Chitrahaar and Sunday Movie on DD being eagerly anticipated, and sports being practiced in the neighborhood park.

Alas, the latter part of the 1990s and the new millennium changed everything. The first decade saw the introduction of mobile phones, the Internet, multiple television channels, the latest brands and gizmos, alternative entertainment and vacation options, QSRs and chain restaurants, glitzy malls, single malts, wine and cheese pairings, Jazz evenings, weekend getaways to beach resorts, summer cruises, SUVs, and countless avenues to splurge aside from petrol, which was approaching the triple digit mark.

We had suddenly shifted from, “On what do I do with my earnings, there are no spending avenues, let me just save or buy an asset,” to a different league of credit card debt and EMIs for home appliances and mobile phones. The days of getting a movie, cola, and samosa for Rs 5 were ended.

Computerization, digitization, PAN, and AADHAR in the present decade have resulted in increased tax compliance, but no more savings from tax avoidance.

Who could have predicted all this?

A double whammy: an increase in expenses owing to the abundance of pleasures turned to “necessities” and a decrease in revenue due to taxes.

That is how life is: full of wonderful uncertainty and upheavals.

They define inflation as non-legislative taxes. It’s when you spend Rs 500 for a Rs 100 haircut, which used to cost Rs 25 with hair.

And most investors expect nominal inflation and a gradual drop in the cost of living when budgeting for retirement, children’s education, marriage, and so on.

Education expenditures have increased by more than 100 times in the previous 20 years, in addition to the costs associated with tuition and coaching programs.

Marriage expenditures, particularly those associated with North Indian weddings, have skyrocketed, making it increasingly impossible to predict future rises.

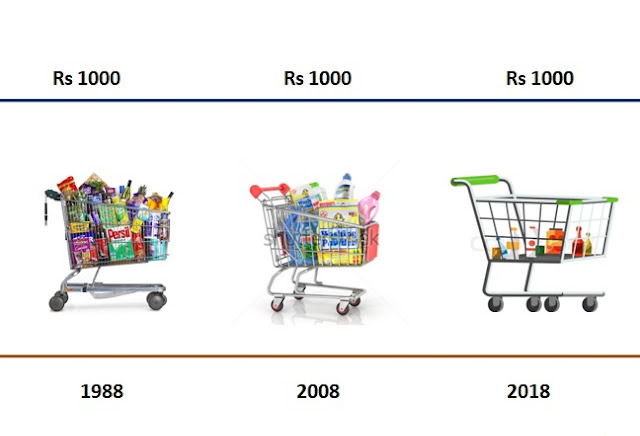

Some individuals comprehend compound interest, but the majority do not recognize the “de-compounding” effect of inflation on money.

As overall costs rise, the consumer’s purchasing power declines. Inflation takes away what compound interest offers.

To put it another way, inflation is practically the inverse of compound interest; because each year’s inflation builds on the previous year’s inflation, the impact is identical to compound interest, and your spending will rise exponentially.

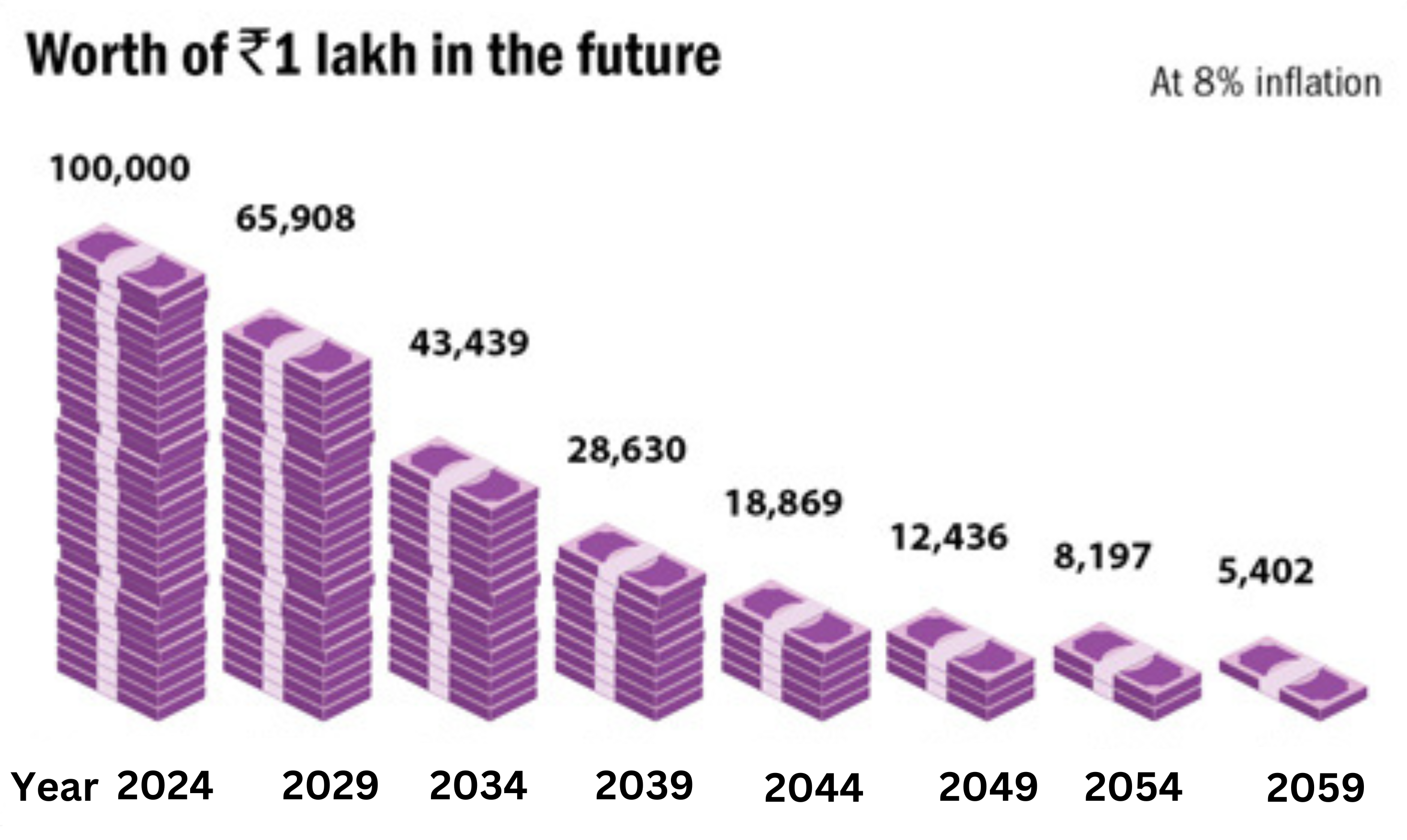

Inflation gradually takes away at your money. We all know this, yet we fail to incorporate it into our savings and investing decisions, as seen in the graph below.

A simple 7% inflation would cut our corpus in half in ten years, and similarly, our present costs will double every ten years.

A safer 6% inflation rate will reduce a Rs 1 crore corpus to 54 lakh after ten years, 29 lakh after twenty years, and 16 lakh after thirty years.

This 6% or 7% inflation is the government-sponsored WPI, CPI, or, at most, food inflation. Healthcare, education, cost and style of life, marriage expenditures, and other expenses are predicted to increase by 12-15%, notwithstanding changes in spending patterns over time.

Even with a Rs 1 crore retirement corpus, a 10% rise in consumption each year and a 7.5% return will entirely deplete your corpus in 13 years, leaving you powerless at the age of 73.

Taxation is another major destroyer of the targeted corpus. The expression goes, “a Fine is a tax you pay for doing wrong & a Tax is a fine you pay for doing right.”

In addition to the earnings from selling investments, you must pay taxes on any interest, dividends, rental, or other income you get.

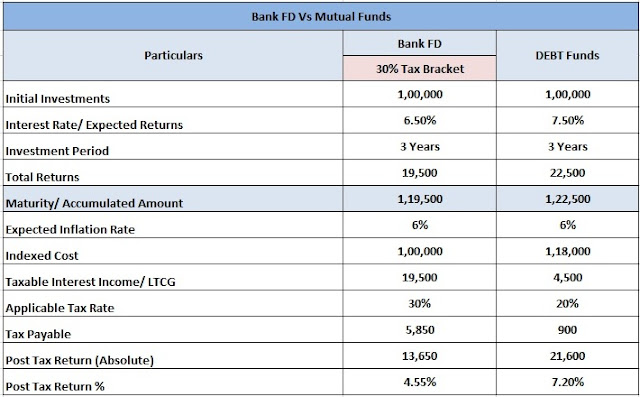

Aside from directly lowering the corpus, it has a wide-ranging impact. Most investors I’ve encountered compare FD results to those of other asset types without considering tax implications. A healthy comparison of Apples vs Apples can only be made using post-tax returns from different asset classes, as shown below.

As seen in the above example, the compounding effect will be fairly significant over time.

The recent inclusion of a 10% tax on LTCG (long Term Capital Gains) in the latest budget means that your investment plans must raise either the investment amount or the projected return by 10% to meet the intended target.

As a result, the first guiding principle of any financial planning must be that your target for post-tax investment return should exceed the projected practical inflation estimates, rather than the Government-sponsored figures of low single digit inflation, or you will end up compromising your child’s education or relying on your children for a “comfortable” retirement.

Better returns may be attained not just by taking on more risk, but also via better tax planning and investment.

It is best to err on the side of caution when choosing the objective, trying to save somewhat more than the expected number.

Plan your investments, take inflation and taxes into consideration, and then pursue your ideal aspirations.

Happy investing!

Stay blessed forever.